The European Union has proposed a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and push its trading partners to decarbonize their manufacturing industries. The CBAM will be implemented in two phases. Starting from October 1, 2023, exporters of steel, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, hydrogen, and electricity, including India, will have to share emission data with the EU. From January 1, 2026, the EU will begin collecting CBAM as an import tariff from “Dirty” goods. The CBAM tax is estimated to be a 20-35% tariff equivalent, which is far higher than the EU’s average import tariff of 2.2% for manufactured products, says a report by the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI), a New Delhi-based think tank.

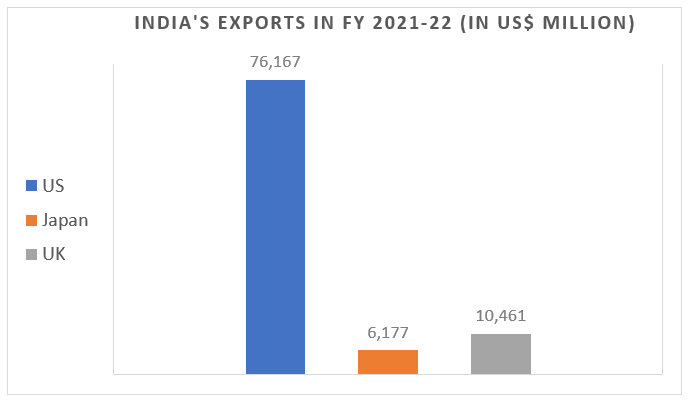

CBAM is expected to heavily impact India’s iron, steel, and aluminum exporters, as 27% of the country’s exports of these products go to the EU, amounting to $8.2 billion in CY 2022. By 2034, the EU plans to expand CBAM to all items. Several advanced economies, including the US, the UK, and Japan, are considering imposing similar carbon taxes on imports.

“India sees CBAM as protectionist rather than climate intervention and is looking for ways to counter it. However, the irony is that CBAM revenues will go to the EU’s budget. In other words, CBAM is a way of making higher tax on imports from developing countries and fund the EU’s climate transition”, says RV Anuradha, an expert in international economic and environmental laws.

At the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) in Washington, DC, on April 10, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman criticized the EU for crafting a policy that would enable an additional flow of funds from developing nations to the EU. The FM said, “So, my non-green steel is okay for you as long as I pay extra. That extra is not coming for me to convert my dirty steel into green steel, whereas I am given the comfort that ‘you may export to me (EU) and I will buy the dirty steel if you pay more. And what will I (the EU) do with that money? I will convert my dirty steel to green steel’.” Through CBAM, the EU is saying that any country wishing to export to the EU needs to replicate its requirements for emission reductions and pay the price for carbon emissions as determined by the EU. She also said “I am sorry to speak like an activist, but that’s how it looks”.

Once the policy kicks in, exporters to the EU, such as the Steel Authority of India and Vedanta, will have to bear a substantial additional burden. This could have a significant impact on India’s export growth. Ajay Srivastava, founder of GTRI and former Indian trade service officer, believes that CBAM should be the top agenda for India’s free trade agreement negotiations with the UK, EU, and Canada. “Carbon border tax will make FTAs with developed countries one-sided”. For example, 85% of India-Japan trade occurs at zero import duties. When Japan implements such a tax, Japanese products will continue to enter India at zero duties. Still, Indian products must start paying high carbon tax even though regular customs duties are zero (due to the FTA).”

“India should adopt a similar measure like CBAM but the formula should be per capita carbon emission and not total emission,” says Abhijit Das, former head of the Centre for WTO Studies, New Delhi.

Despite India not being a big polluter on per capita basis — its per capita emissions are lower than the world average — it has promised to achieve net zero emissions by 2070. Yet when it comes to the EU’s carbon tax, India is opposing it tooth and nail. As experts have pointed out, the very foundation of the carbon tax — that the EU will accept dirty steel or aluminium a long as it is bundled with some euros — is faulty. And if those euros are deployed to clean Europe’s dirty industries, it is tantamount to reverse climate financing from a poor nation to a rich bloc.

– Sourced from: The Economic Times (Apr 23, 2023)